Polymarket vs Forecasting: Geopolitical Shifts in 2026

In a world defined by volatility and shifting geopolitical tides, decision-makers are increasingly desperate for a signal through the noise. Open platforms like Polymarket have positioned themselves as the ultimate source of truth, claiming that market-driven "wisdom of the crowd" is the most accurate predictor of the future.

However, decision science suggests a different story. Markets are often prone to irrational exuberance, liquidity gaps, questionable resolution decisions, and emotional bias. To prove that the Swift Centre provides a more reliable signal, we put our world leading team of forecasters to the test.

We identified five key markets on Polymarket that were not only decision-relevant but appeared fundamentally mispriced (i.e. either overbought or undersold). By pitting our team against these live market prices, we aimed to demonstrate that the Swift Centre’s methodology offers superior analytical rigor, better question design, and, ultimately, higher accuracy than the implied forecasts of the world famous prediction market.

Key takeaways (Swift Centre forecasts made before 9:00 on Tuesday 27th January 2026)

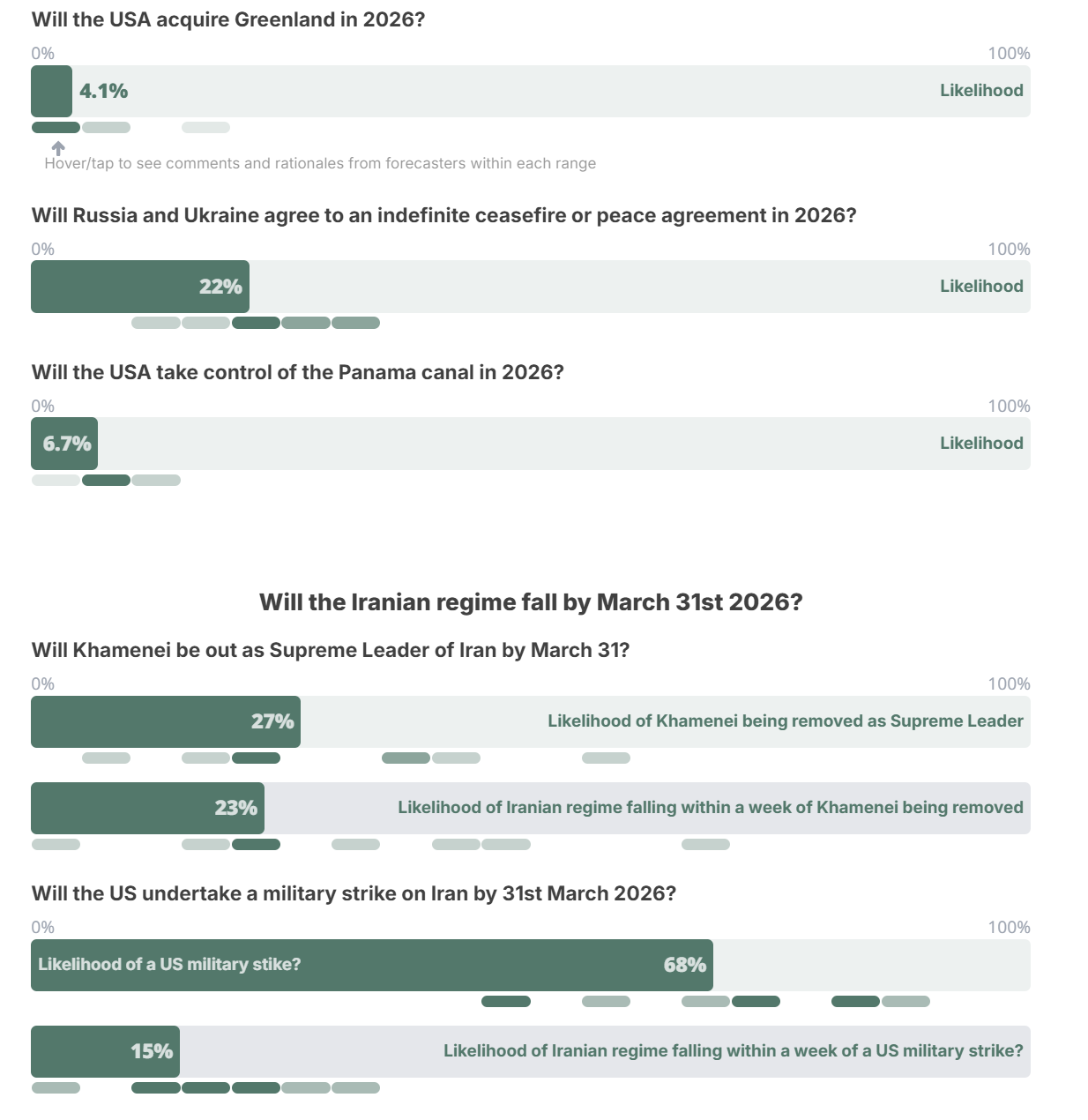

The Swift Centre forecasters saw a ~4% chance of the United States acquiring Greenland in 2026, distinctly lower than the 12% that was on the relevant Polymarket question.

The likelihood of Russia and Ukraine agreeing to an indefinite ceasefire of peace agreement this year was forecasted at 22%, considerably lower than the ~43% odds on Polymarket.

The forecasters saw a ~6.5% chance of the US taking control of the Panama Canal in 2026, lower than Polymarket’s odds of ~15%.

The likelihood of Iranian Supreme Leader Khamenei being out of power by the end of March 2026 was pegged by the Swift Centre forecasters at 27%, compared with Polymarket’s 26%, while the likelihood of the US undertaking military strikes on Iran by the same date was estimated at 68%, notably higher than Polymarket’s ~55%.

On both these questions, the forecasters saw an under-25% chance of the Iranian regime collapsing within a week of either event occurring.

Trump’s designs on Greenland

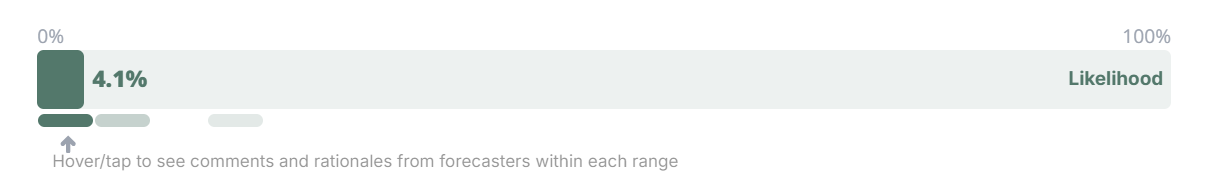

Will the USA acquire Greenland in 2026?

Likelihood: 4.1% (range 2%-15%)

Polymarket: 12%

All the Swift Centre forecasters saw the US “acquiring” Greenland this year as quite unlikely, with a median likelihood of 4.1% and no forecasts exceeding 15%, though they also paid close attention to how “acquisition” was being defined in the context of this question (and how various definitions would be interpreted on Polymarket).

Most interpreted the question as resolving positively only if sovereignty over a majority of the territory were transferred to the US. There was general agreement that the smaller concessions reportedly proposed in the recently announced “framework agreement” for negotiations would not qualify.

“Even if this does include the US gaining sovereignty over ‘small pockets” of land so it can build military bases,” one forecaster wrote,“this wouldn’t be equivalent to acquiring all of Greenland…. I think we’ll know it when we see it, and an official announcement that lacks credibility wouldn’t count in my mind (even if it would in Polymarket’s judgment).”

Most of the forecasters began their rationales by stipulating the sheer implausibility of Greenland being acquired by the US, taking account of both domestic and international opinion (“Pretty much everyone is against it.”) and geopolitical basic realities (“It is insanity.”). Several echoed one forecaster’s point that there is “a long history of US interest in Greenland (1867, 1910, 1946, 1955 and Trump’s two terms in office)”, but none suggested that Trump’s present motivations were strongly grounded in this history.

Collectively, the forecasters listed off many factors that would be expected to dissuade a rational US administration from pursuing a takeover of Greenland, including:

The well-attested fierce opposition of the Greenlanders themselves;

The uncommonly “united front” the European states have so far presented against the threat; the lack of support for this policy among the US population, Republican elites, and even members of the Trump administration (“taking Greenland is a level of political suicide that could get Trump booted from office”, one forecaster wrote);

The potential economic consequences of pursuing such a direct confrontation with Europe (one highlighted the threat of European countries “further decoupling their economies away from the US and the dollar,” making US debt more expensive); and above all

The fact that a seizure of Greenland would constitute an unprecedented attack by the US on a treaty ally and could be fatal to the US-anchored NATO alliance.

Several forecasters noted that the Trump administration itself now seems to be backing away from the most aggressive iterations of this policy. One forecaster (3% likelihood) wrote that “recent signals from the Trump administration have been fairly de-escalatory”, and another (7% likelihood) said that “I think we have reason to be optimistic that the Trump administration has backed off of full acquisition … for the time being.” Several highlighted the cross-cutting dynamics among Trump’s advisors: “[Stephen] Miller is probably the driving force pushing for US ownership of Greenland,” one wrote, while the “choice of Rubio, Vance and Witkoff to conduct further negotiations strongly suggests to me that these three would prefer not to press the issue of full US ownership.”

The most plausible avenue for the US to “acquire” Greenland, as most of the forecasters saw it, is not military invasion but a purchase. “The baseline here is a low probability by use of force, especially against treaty-based allies,” as one put it; another pointed out that it was possible that “no general or military officer would be willing to lead such an effort.” Interestingly, the very same logic, considered alongside the US’s disproportionate wealth, led at least one forecaster (15%) to argue that a purchase is a possible outcome:

“If Trump were to pursue ownership of Greenland again, then I think it’s very likely that Denmark would sell Greenland to the US, simply to avoid the possibility of military conflict with the US and the weakening of NATO.”

A purchase would be in keeping with Trump’s oft-stated preoccupation with “ownership”, which might also predispose him to reject any potential concessions by Denmark structured as treaty-based sharing.

Broadly speaking, though, the forecasts on the higher end of the likelihood range tended not to fixate on specific paths to a positive resolution but rather emphasised the unpredictability of the situation and of Trump’s moves. “This is a highly dynamic situation” was the concluding line of one forecaster’s rationale (7%); several others offered similar caveats.

It seems that Trump’s sheer unpredictability was enough to convince the forecasters that the likelihood of Greenland being acquired by the US was not negligible, despite all the factors militating against it.

Stalemate in the Russia-Ukraine war

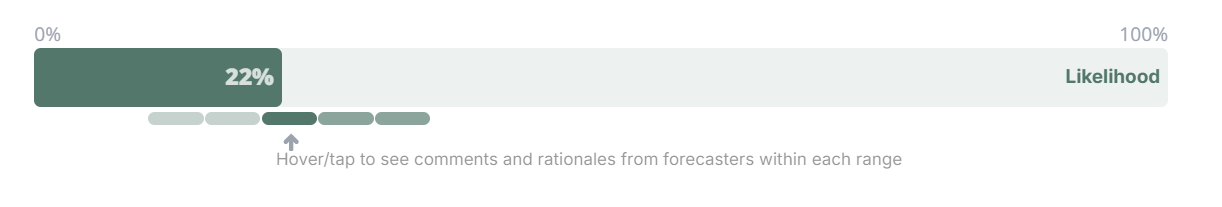

Will Russia and Ukraine agree to an indefinite ceasefire or peace agreement in 2026?

Likelihood: 22% (range 12%-33%)

Polymarket: 43%

On this question, the Swift Centre group’s median forecasted likelihood of 22% was notably lower than the analogous Polymarket odds, which was at 43% on the day they forecasted. In their rationales, the Swift Centre forecasters were consistent in describing the current situation as unlikely to change in the near term: if not a deadlock, in their view, it is a structurally balanced system in which decisive changes are less likely than gradual shifts.

The forecasters agreed that as of now neither Russia nor Ukraine has a strong incentive to make concessions, and that military facts on the ground are unlikely to force hands on either side. While the outlines of a potential agreement are not hard to make out, the forecasters were doubtful that any such deal will be reached before the end of this year. As one forecaster (21% likelihood) put it:

“Over the previous four years, there have been multiple false dawns when it comes to the negotiation of a ceasefire or even peace agreement. I am not optimistic about this occurring this year.”

The group’s consensus view was well captured by one forecaster’s description of the status quo as a three-sided system composed of Russia, Ukraine and NATO, one in which all sides are “very much wanting to see the end of the war but being restrained by the perceived need to save face: NATO almost constitutionally is unable to admit a defeat in the war it catalysed, Ukraine cannot admit an official defeat in the form of losing large territories, and Russia cannot admit a defeat in not fulfilling its original goals in the war it started…. [All of them] are powerfully incentivised to kick the can of this war down the road.”

The forecasters tended to start from the historically grounded general proposition that wars between balanced forces are more likely than not to continue in any given year. Several forecasters started reasoning off of baseline probabilities of 10%-20%, based on historical data or Laplace’s rule of succession. Others seemed to generally concur with these baselines.

While the forecasters all described the current situation as fairly stable, they differed somewhat on how they saw the various forces possibly tilting over time, especially when it came to describing US influence and Trump’s personal stance. One forecaster (16% likelihood) stated flatly that “Trump is not pressuring Putin,” but another (20% likelihood) argued that “Trump has consistently been working to undercut Russia’s economic condition.” There was no strong consensus on the role that Trump himself is likely to play in the coming year. “When Trump’s attention is on something, that can be a very powerful force,” one wrote, but another forecaster doubted that Trump would withdraw military support for Ukraine “because of the [likely] backlash from within the Republican Party.”

With Trump’s stance hard to pin down, the forecasters tended to focus more on the motivations of Putin and Zelensky. There were subtle differences in how the forecasters assessed the likelihoods of each leader changing his position.

Putin’s bargaining position, and by extension Russia’s, was probably the area of sharpest focus and the most implicit debate. How intransigent can Russia afford to be? One forecaster wrote that:

“it’s very likely that Putin still has the original war aims he outlined in his invasion speech: to conquer and occupy all of Ukraine and depose the current government…. [H]is bet seems to be that he has the resources and the men to wear Ukraine down. There is little incentive for him to stop the war.”

Others implied that Putin might eventually prove somewhat more susceptible to pressure, whether from other players, from the situation on the ground, or from the strain on the Russian society and economy. One forecaster noted that “both sides seem to struggle with personnel” and that Russia is reported to be suffering more 1,000 casualties per day; another (21% likelihood) shared evidence that Russia’s economy “has really begun to hurt … and it is more likely that both sides are tiring of continued war.” Overall, the forecasters tended to see Putin’s position as fundamentally dug in – “I’m struggling to imagine something that would make him change his mind on this,” as one put it – but potentially more susceptible to pressure as time goes on and war costs mount. Either way, they were sceptical that Putin’s position would shift this year.

By contrast, there seemed to be less debate among the forecasters that Ukraine, while not having a strong incentive to make concessions now, would be forced to make compromises if the other players’ positions aligned to that end. In one forecaster’s view:

“this all adds up to maybe a 1 in 5 chance of a peace agreement being reached this year, with the most likely possibility being that Ukraine is forced to make a deal in some way, one which gives Putin the option of restarting the war in the future.”

The forecasters agreed that, all else being equal, Russia and Ukraine are both likely to hold the line in 2026, but their rationales suggested that Ukraine is slightly more likely to give in sooner because it is vulnerable to shifts in the positions of its allies – a vulnerability that, in the forecasters’ view, seems to translate to a roughly 20% likelihood of Ukraine being forced to surrender this year.

The US probably won’t retake the Panama Canal

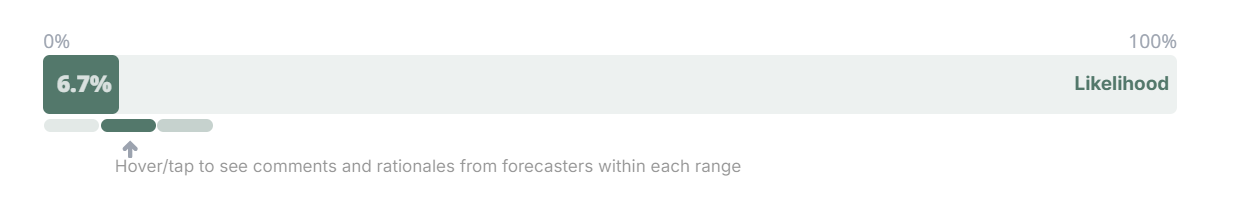

Will the USA take control of the Panama Canal in 2026?

Likelihood: 6.7% (range 3%-12%)

Polymarket: 15%

The Swift Centre forecasters saw the likelihood of the US taking control of the Panama Canal this year as comparable to that of the US acquiring Greenland this year – under 10% – but their reasoning was very different in the two cases. Compared with the Greenland case, the strategic rationale for the US taking direct control of the Canal is much clearer and the historical precedent much stronger. But the forecasters also agreed that the Panama Canal appears to be less of a priority for Trump and his administration than Greenland has been to date. On these determinative points there was a fairly strong consensus among the forecasters, contributing to the fairly tight band of estimates (3%-12%).

Most of the forecasters reiterated that, as one put it, “the US has a history of engaging in aggressive actions to control Panama to control the canal”. They also agreed on the two main strategic rationales that might motivate the administration to take such an action now: (1) countering China’s increasing influence on the Canal zone and two of its major ports, and (2) more assertively exercising US power in the Americas.

Beyond the basic logic of these rationales, there was little discussion of how compelling they would actually be in the context of US policy today – possibly reflecting the forecasters’ sense that the administration has not laid much policy groundwork for action in Panama, though one forecaster did note that Secretary of State Rubio has “previously made it clear that there needs to be some dramatic change here.” The forecasters were more attentive to Trump’s personal level of investment in the idea. Most of the forecasters thought that Trump is not highly preoccupied with this issue. Several forecasters noted that while Trump has “expressed interest” in taking control of the Canal in the past, the idea has not been frequently mentioned by the administration since he returned to office. Another said that while “Trump has made statements,” he “seems to have rowed [them] back somewhat. It is not clear that this is a high priority issue for Trump.” On the other hand, some forecasters speculated that a Panama Canal operation might be presented to Trump this year “as a pacifier to keep [him] from more extreme actions such as taking Greenland.”

The forecasters tended to set aside the murky question of how motivated the administration might be to attempt a takeover and paid more attention to its capability of executing one, comparing this prospect with a notional takeover of Greenland and the recent operation in Venezuela. On one point the forecasters were in clear agreement: a Panama Canal operation would be easier (“both militarily and politically,” one forecaster wrote) than a Greenland acquisition, but more taxing than the Venezuela operation as it has unfolded so far. Another forecaster’s assessment was that “this is easier to do than Greenland as no one cares enough about Panama to protect it,” and that “China’s relative control of the canal is worrying and would make it an easy sell to the American people.” At the same time, the forecasters generally recognised that “simply making a few strikes” would not achieve the objective of controlling the canal, and that a military operation would likely take “months” and would likely necessitate an invasion.

Several forecasters argued that the US is already involved on too many other fronts to undertake such an effort now.

“I think there is simply too much on the US’ plate at the moment, between Venezuela and the potential for actions in Iran, Mexico, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, Nigeria, and even Greenland,” one forecaster wrote.

Another noted reports that current operations around Venezuela and Iran are already “putting a strain on military resources.” If it becomes necessary to make a choice among targets in this region, one forecaster argued, taking control of the Canal “is almost certainly a lower priority [for the US] than regime change in Cuba, which would be a massive event all its own.”

Finally, the forecasters also considered whether the threat of a reaction from China might deter the US from taking action in Panama. Generally, the forecasters did not identify China’s potential response as an immediate deterrent; one wrote that “China is certainly not going to send troops to protect [Panama].” Another forecaster, after acknowledging that “China has a substantial interest in the Panama Canal, so its acquisition might not happen without some pushback,” went on to observe that “China does seem to be ceding some interest in the Americas in the hope that the US will take less interest in Taiwan and the South China Sea.”

Will the Iranian regime fall by the end of March?

The forecasters were asked to consider two conditional scenarios related to the likelihood of the Iranian regime falling in the first three months of this year. It was notable that in both cases, the Swift Centre forecasters were very cognizant of the tight time frames stipulated by the questions – often noting, for example, that their estimates would have been higher if a question’s time frame had been the entire year or longer than a week.

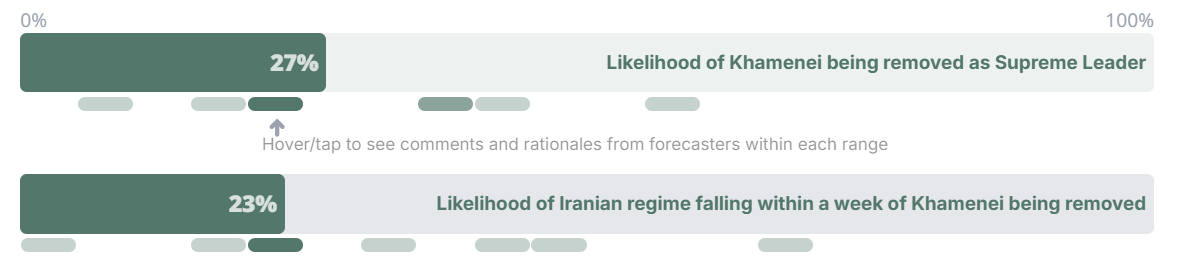

1. Will Khamenei be out as Supreme Leader of Iran by March 31?

a. 27% likelihood of Khamenei being removed as Supreme Leader (range 9%-55%)

Polymarket: 26%

b. 23% likelihood of Iranian regime falling within a week of Khamenei being removed (range 1%-65%)

There was a wide distribution of views on the likelihood of Khamenei being removed in the next few months, with estimates ranging from 9% to over 50%. Many forecasters saw a substantial likelihood of Khamenei being out of power sometime this year, but fewer saw it happening within the next two-plus months.

Almost all the forecasters noted that, at 87 years old, Khamenei is at a non-negligible risk of natural death within the year, though according to several of them the risk within the first three months is likely in the low single-digits.

Beyond that consideration, those on the lower end of the distribution seemed to base their reasoning on the comparatively low historical rates of authoritarian or theocratic leaders losing power in a given year, let alone a given three-month period. Several forecasters also stressed that the likelihood of an attempt (on the part of foreign adversaries) to remove such a leader from power is not the same as the likelihood of the attempt actually succeeding, pointing to the examples of Muammar Gaddafi and Saddam Hussein. “I think it is very likely there will be an attempt to unseat him,” one forecaster (38% likelihood) wrote, but “where I am hesitant is whether it will succeed.”

Across the distribution, the forecasters generally agreed that there were multiple avenues by which Khamenei could plausibly be removed this year: natural death, assassination, targeted strike, coup, revolution. Several focused on the key role in the regime of the Revolutionary Guards (IRGC) and how likely it was that the IRGC might be compelled to withdraw their support from Khamenei before April. The forecaster with the highest estimate (55%) wrote that:

“I don’t think it’s likely that the regime will collapse because of protests alone; instead, I think it will collapse either when the enforcement arm of the regime is no longer willing to crack down on dissent, or in the event of an internal coup.”

But another forecaster saw it as “very unlikely that there is an internal threat to Khamenei that could topple him alone.”

In general, the forecasters saw Khamenei losing power as most likely to result from the simultaneous combination of external action (military strikes by the US and/or Israel) and internal elements of the regime breaking from him (in the context of widespread popular discontent). While at least one saw such a scenario happening “sooner rather than later,” the group as a whole seemed to see a scenario with so many prerequisites as substantially more likely to materialise by the end of this year than before the end of March.

On the conditional question, the forecasters were, on the whole, fairly doubtful that entire regime would fall within such a short time of Khamenei being removed from power, largely based on historical baselines. “Seven days is very short,” one wrote (1.2% likelihood), and “it’s clear that cases like Ceaușescu are … huge outliers.” That said, the forecasters’ estimates were very scenario-dependent. “Coups result in rapid change,” one forecaster (65% likelihood) pointed out, “and a Venezuela-style removal of Khamenei could also cause rapid regime change.” Another forecaster (20% likelihood) argued the fact that “there is no established leader or group that is openly challenging the current regime” probably makes a rapid transition less likely, unless “the US and Israel have already made contact with an alternative and have worked out a deal.”

The IRGC was again identified as likely to play a key role – either slowing down post-Khamenei regime change or accelerating it. One forecaster pointed out that “[t]he IRGC has more than 100,000 members and they could still try to exert control, and Khamenei has in any case probably been less involved in decision-making in recent months because of his old age”; on the other hand, they wrote, “it’s also possible that, as in Venezuela, the US is willing to work with someone else from within the existing regime as long as they comply with certain demands.”

The forecaster who saw the highest likelihood of a very rapid regime change (65%) characterized Iran’s entire society as already primed for a wholesale change of governance:

“I think most elites, in addition to most of the population as a whole, are tired of the current regime’s implementation of religious rule and would not want to start another regime that places religious leaders in charge.”

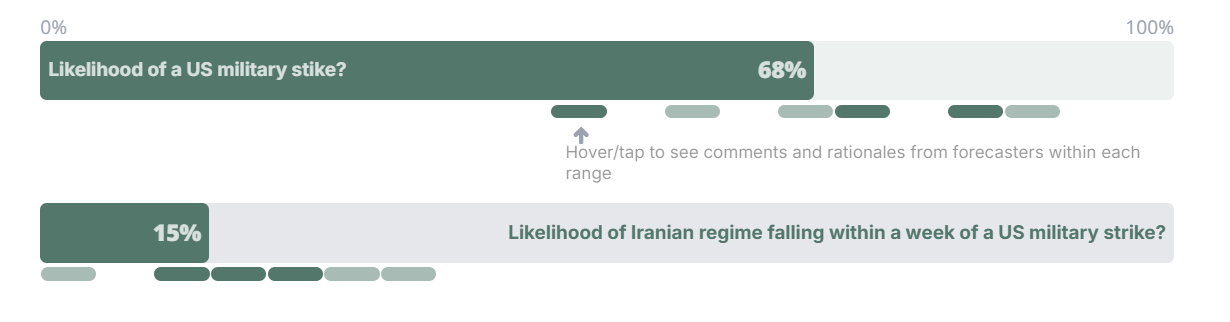

2. Will the US undertake a military strike on Iran by 31st March 2026?

a. 68% likelihood of a US military strike (range 45%-85%)

Polymarket: 55%

b. 15% likelihood of Iranian regime falling within a week of a US military strike? (range 2%-33%)

As a group the Swift Centre forecasters saw a substantial likelihood of the US striking Iran before April, with most of the estimates coming in at 50% or more. The three factors that most of the forecasters identified as making a strike more likely were the continuing US buildup of military assets in the region, the recent precedent of the Trump administration taking military action against Iran, and the potential window of opportunity for regime change created by the massive wave of protests there.

The short, two-month time frame stipulated in the question was the most commonly cited countervailing factor, simply because the base rate for a military attack has to be lower when the window is so tight – but timing seemed to be less of a constraint on this question than it was on the others in this set. Some forecasters noted that logistical problems caused by the recent winter storm in the eastern US are delaying force deployment to the Middle East, potentially testing the question’s time frame, but at least two thought that US forces would be ready well before March 31. One forecaster wrote that “it is reasonable to assume that within about 3-4 weeks, the U.S. will have sufficient assets in the area to effect a strike.”

The forecasters had varying interpretations of Trump’s declarations that the US “might not have to use” force, which the most sceptical forecaster took to mean that the US “is likely to use other options to the extent that they think they’re tenable.” Several also pointed out that the US might have missed its opportunity to strike when the protests in Iran were at their height, making future action less likely:

“Surely the time to [attack] was in the last two weeks. As we move away from that (and [Trump’s] rhetoric softens) the chance of conflict falls.”

One forecaster who had a high estimate (80%) pointed to the apparent absence of clearly defined goals as the reason why their estimate was not even higher. “What exactly would be accomplished by an airstrike?” they asked.

“What to attack? This ambiguity is the reason I am not higher on this question. The U.S. could destroy more military assets, but it is not clear if that would be sufficient to unseat the current government. They could go for decapitation strikes, to kill Khamenei and others, but would that be enough to accomplish regime change?”.

Nonetheless, the clear evidence that the US military is preparing for military action in the region was enough to keep this forecaster’s estimate on the high side.

Several forecasters wrote that they expect any attack to be comparatively limited and symbolic, potentially targeting “individual IRGC leaders” and aiming to demoralise and destabilise the regime rather than substantively degrade its military capacity. This reflected a general view that any strikes would be more of a pressure instrument than a comprehensive military assault. Indeed, this same logic was cited by some as one reason why an attack was less likely than it might seem: one wrote that “I’m not higher than 70% because a deal negotiated behind the scenes is possible, as is a coup that may pre-empt a strike.”

While the median forecast of the likelihood of a near-term strike was quite high, the forecasters were less convinced (15% median) that the Iranian regime would fall within a week of a strike. No estimate exceeded 33%. Once again, the time frame was too tight for many forecasters to be comfortable with a high estimate. Echoing several others, one forecaster asserted that:

“Regimes almost never fall within a week of a US strike. Strikes might be very precise or take place over weeks.” Another pointed out that a “rally under the flag” effect might “make the regime stronger in the very short term”.

A third speculated that the reportedly brutal suppression of the recent protests may have simultaneously cowed the opposition-minded public and left regime elites feeling less safe switching sides – a dynamic that might take time to unwind.

But on this question, too, several of the forecasters made an exception for a scenario in which the US and other outside players have already covertly reached a deal with a potential successor. One wrote:

“I am revising upward slightly because I believe that the US will most likely want airstrikes and other military actions to be after they have found an Iranian leader that will replace the current regime. And with that, I believe the probability is a bit higher we would see immediate regime change under this scenario.”