China, Taiwan, and TSMC Risks to 2027

If you have comments on this analysis, or would like to see these questions re-posed with different timeframes or conditional scenarios, please drop us a line at [email protected]

Key Takeways:

The Swift Centre Forecasters see a 9% chance of a Chinese blockade of Taiwan by mid-2027. All major actors still benefit from the status quo and a blockade is seen as a high-risk, limited-upside move in this timeframe.

A formal sovereignty referendum or constitutional change in Taiwan by 2027 is viewed as unlikely (3.1%), barring extreme coercive scenarios of imminent defeat or capitulation.

Taiwan’s defence spending is expected to rise steadily but not explosively, at ~3.5% of GDP range in 2027, (below the trajectory implied by the government’s goal of reaching 5% by 2030) constrained by domestic politics, accounting tricks, and practical procurement limits.

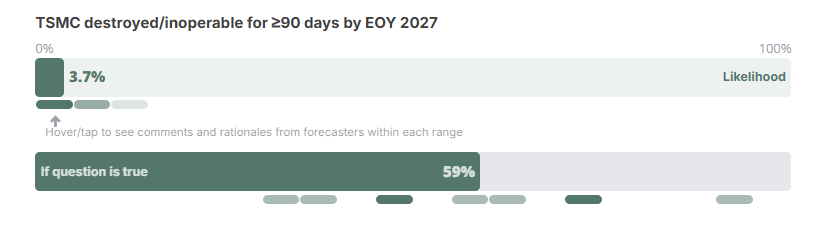

Absent a crisis, forecasters think TSMC is resilient: the chance of any Taiwan fab being destroyed or offline for ≥90 days by 2027 is only at 3.7%, but that jumps to 59% conditional on a blockade, possibly via energy and input chokepoints rather than direct strikes.

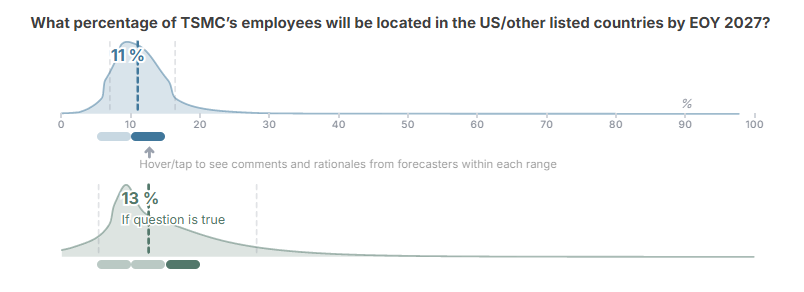

TSMC’s workforce is expected to internationalise only gradually: by 2027, forecasters anticipate a modest increase to roughly 10-12% of employees located in the U.S. and “allied” countries, with Taiwan remaining the dominant hub. Conditional on a blockade, the median rises only slightly (to ~15%) reflecting wider uncertainty rather than a major shift in workforce location.

Question 1: Will China blockade Taiwan by mid-2027?

Forecasters put the probability of a Chinese blockade of Taiwan by mid-2027 at 9%, with estimates ranging from 4.9% to 15% – a “low but not negligible” probability. Forecasters naturally view a blockade as easier to mount than a full invasion, but still a major step with high risks of escalation, economic disruption, and confrontation with the U.S. and its allies.

Status quo is attractive, blockade is high-risk for limited gain

Several forecasters started from the view that all actors involved broadly prefer the current status quo, and that the upside of a blockade is limited relative to its risks. One (at 9%) further noted that even if a blockade “goes 100% smoothly and peacefully for China (a big if), the upsides seem limited: national pride and fulfillment of the promises by the CCP,” while “the downsides are significant: loss of a lot of trade and a potentially huge and unpredictable conflict, all the way to up to getting nuclear.”

Others in the same probability range (8-8.5%) emphasized that China can “live with the status quo quite well,” and that “the Taiwan question is arguably more valuable to them unsolved than solved.” Another pointed out that Xi is not under immediate time pressure, arguing that “he is not in the same rush as the politics of democracies demand” and is more likely “to plan strategy on a longer term and get PLA forces perfectly ready and strong enough before attempting anything over Taïwan.”

On this view, rising military exercises and provocations were interpreted as actions that “ensure readiness to all possible scenarios – far from being signals of the imminent blockade/invasion.” However, not all forecasters agreed: some saw the increasingly elaborate PLA drills as “rehearsal” activity that could shorten warning times for either a blockade or invasion.

A few forecasters also noted that Beijing may continue prioritising political, economic, and information-domain pressure (what some describe as attempts to “take the island from within”) reducing the incentive to launch a disruptive, high-risk blockade in the near term.

Is a blockade tied to an invasion?

A central question for forecasters was whether a blockade should be seen as effectively synonymous with an invasion attempt (a blockade used to prepare the battlespace for an amphibious assault) or as a distinct strategic option (e.g., a campaign designed to coerce Taiwan without immediate escalation). They referred to recent strategic assessments that similarly frame a standalone blockade as a viable alternative to invasion, noting that it carries fewer military risks and may be less likely to trigger immediate U.S. intervention.

Some forecasters treated the two as tightly coupled. On said: “a blockade by China would either be a part of or all but inevitably lead to a full military attempt.” Given this, they considered “the likelihood of a blockade to be nearly identical to that of an invasion of Taiwan,” and set their probability at 15%, driven by Xi’s ambitions, PLA recent military exercises or “rehearsals,” and a perceived window during the current U.S. administration.

By contrast, other forecasters did not consider a blockade scenario as necessarily being synonymous with an invasion one. They envisaged a standalone strategic blockade as a way to “test the waters, take the temperature, and offer paths either for further escalation or de-escalation in a face-saving manner.”

A forecaster at 11% offered a different perspective grounded in historical examples. They treated blockades as de facto acts of war: “Blockades during the previous 100 years have ended up being an act of war in practice, not a means of intermediate control.” This forecaster reviewed past blockades and concluded that it is “highly questionable if a blockade could achieve subjugation of Taiwan without either resulting in war from attempts to break it, or become overly burdensome to China and force its end.” From this angle, a blockade is more likely to be “a prelude to air strikes and invasion.”

Constraints, deterrents, and timing

Forecasters also stressed practical and strategic constraints that dampen the near-term risk and pull many estimates into the 5-11% band.

During the discussions, blockades are described as “relatively rare, extremely complex to pull off from the blockaders point of view,” even with modern ISR support. On logistics, one forecaster at 5.6% noted that a robust blockade of Taiwan would be “a huge undertaking”, adding that “Kaohsiung port is one of the top 25 busiest ports in the world […] Taiwan imports effectively all of its natural gas via LNG […] and around 70% of the islands food comes via shipping”. Another forecaster similarly doubted China’s readiness for an invasion-plus-blockade operation, pointing to “many new weapons systems […] not yet in full production, much less well tested,” and the difficulties of overcoming U.S. and Japanese resistance at sea and in the air.

Deterrence also featured prominently in the discussions. One forecaster highlighted the elephant in the room: China’s ~600 nuclear warheads, with plans to grow its arsenal, and noted uncertainty over “whether China considers it important to approach nuclear parity with the US before threatening an invasion of Taiwan, or whether they consider their current nuclear status to be sufficient to deter full scale US intervention in a Taiwan conflict.” Others (around 10-11%) emphasised longstanding U.S. commitments and signals, arguing that “given a multitude of US actions in military support of Taiwan […] prior administrations have made it reasonably clear the US would respond militarily.” Here, there is partial divergence on how to read U.S. policy. Most forecasters treated U.S. commitments as a continuing deterrent. But a forecaster (at 11%) floated the possibility of a “G2”-style understanding, where the U.S. and China tacitly divide spheres of influence, raising the risk that Washington might “put Asian ally interests on the sidelines,” or at least appear less committed, potentially emboldening Beijing..

Finally, several forecasters noted the short horizon to mid-2027 and seasonal “windows of opportunity” for large-scale operations. One suggested that “there are maybe two windows of opportunity per year for China to invade Taiwan,” and that current indicators (“stockpiling, unit movements, PLA personnel policies, asset freezes and so on”) do not suggest an imminent campaign. Another expected risk to be higher in the second half of 2027 than before mid-2027, citing PLA guidance to be ready by 2027 and the time needed to consolidate loyal military leadership.

Question 2: Will Taiwan schedule or pass a sovereignty-related referendum or constitutional amendment by 31 December 2027?

Forecasters assigned a 3.1% probability, with opinions clustered between 1.1% and 7%. Forecasters overwhelmingly judged such a move as highly unlikely under the status quo, politically explosive, and offering little strategic benefit. Even under coercive pressure, most assess that Taiwan would have higher priorities than organising a sovereignty vote. The consensus implied that only extreme scenarios of military collapse or imminent capitulation could trigger such a decision.

A vote would be dangerously provocative

Multiple forecasters (with estimates between 1-3%) emphasized that neither the government nor the public has an incentive to initiate a sovereignty-related referendum. One forecaster (5%) writes it “would be very unwise – only giving China pretext while achieving nothing of substance for Taiwan.”

Others noted that both major parties (i.e. KMT and DPP) avoid steps that would anger China or anger the electorate. A forecaster at 1.1% added that independence referendums rarely succeed in Taiwan, and “all it does is infuriate China […] and probably would lose anyway.” At the upper end of the distribution, one forecaster (7%) similarly judged the scenario “extremely unlikely” under normal politics but assigned a slightly higher probability because prolonged pressure from China could coerce Taipei into scheduling a sovereignty vote or passing an amendment that explicitly renounces sovereignty. This coercive path, in their view, is the only realistic route to such an outcome.

Extreme coercive pressure: the most plausible path

Several forecasters outlined that only severe crisis scenarios (blockade, invasion, or imminent defeat) could create conditions where a sovereignty vote becomes possible.

One forecaster at 2.5% argued it has “virtually no chance […] unless there is an attack on Taiwan,” while another (at 3%) suggested the only plausible scenario is one in which China “successfully blockades Taiwan and is dead serious about imminent invasion,” prompting a desperate referendum that effectively amounts to capitulation.

But even in a crisis, some note practical constraints: “if there is a conflict it is fairly clear they are sovereign (or shortly won’t be)[…] if they manage to fight off an invasion, I don’t see the point of holding one anyway” (1.1%).

Some forecasters argued that during a blockade or attack, a referendum would actually become less likely. One (at 3.2%) notes that in such conditions “spending the time for a sovereignty referendum would be a low priority unless Taiwan had already decisively defeated China.” Another at 1.1% stresses that “lining up at a polling station while missiles are flying” is implausible.

Institutional hurdles and referendum failure rates

One forecaster (3%) highlighted that Taiwan’s constitutional amendment process requires 75% of legislators plus a turnout quorum of >50% of eligible voters, making passage extraordinarily difficult. They added that “Taiwan does not have a lot of luck with referendums,” with only one referendum day since 2000 passing any items.

Another forecaster at less than 1% emphasized that both elite politics and referendum mechanics create a near-total barrier: “It’s hard to imagine a situation in which any party […] would pursue such a course […] even scheduling such a referendum […] would be extremely inflammatory.”

Question 3: What will Taiwan’s defence budget be as a percentage of GDP in 2027?

Forecasters put Taiwan’s 2027 defence budget at ~3.5% of GDP in 2027. All forecasts sit in a narrow band between 3.30% and 3.60%, indicating strong consensus on a moderate increase from 2025-26 levels, but not a runaway climb toward the government’s longer-term 5% ambition.

Anchoring on the 2026 jump

Forecasters generally anchored their estimates on the move from ~2.45% in 2025 to a proposed 3.32% in 2026 under new accounting rules, then projected a smaller real increase into 2027.

One forecaster described 3.3% increase in 2026 announced as “a reasonable 50% median scenario” and expected 2027 to be “roughly at the same region,” with escalation scenarios “higher than the 90th percentile.” Another, with a central estimate of 3.6%, expected the ambitious 2026 proposal “along with any proposed 2027 budget” to be pared back somewhat by the legislature, but still anticipated “significant year-on-year growth, especially as the Trump administration is pushing Taiwan to spend more on its defence.”

Others converged around similar numbers: one set 3.47% as a midpoint with a standard deviation of 0.35, another chose 3.5% with a 2026 lower bound and ~3.7% as a 90th-percentile upper bound, and another gave a 2027 range of 3.05-3.95% with a median around 3.5%. Taken together, these estimates point to incremental growth off a higher 2026 base, rather than another step-change.

Accounting changes and “paper” increases

Several forecasters stressed that the big jump to 3.32% in 2026 is partly an accounting artefact rather than a pure real increase in military effort. One noted that “the last increase is mostly an accounting trick,” while another explained that the 2026 figure “includes spending on the Coast Guards and military retirements” that were previously excluded. Under the old standard, they pointed out, “the 2026 budget would only be 2.84% […] for a year-on-year increase of 16%.”

This led to caution about extrapolating linearly from 2.45% to 3.32%. As one forecaster put it, “if you’re creative enough it’s still possible for the spectrum to be widened by 2027 but it does seem unlikely to get an increase of that size again.” Another warned that “what exactly counts as defense spending is often controversial […] it is tempting for politicians to count projects as defense-relevant that really aren’t,” suggesting that headline percentages may overstate genuine capability gains and complicate resolution.

Political constraints, U.S. pressure, and procurement limits

Forecasters broadly agreed that domestic politics and practical constraints on procurement and implementation will limit how far and how fast spending can rise.

On the domestic side, forecasters noted that Taiwan’s plan to reach 5% of GDP by 2030 seems very ambitious, especially given KMT opposition. One highlighted that “the KMT’s chair-elect […] does not want to see defence spending grow unchecked or crowd out other expenditures,” and viewed large increases as potentially provocative towards Beijing. With the KMT holding a plurality in the Legislative Yuan and elections scheduled for 2028, several forecasters expected the Lai administration will “need to make at least some concessions each year and will likely not be able to pass defence budgets as large as it would like.”

On external drivers, forecasters recognised U.S. pressure and arms sales as pushing upward. One noted that Taiwan has felt compelled to increase spending “based on Trump administration actions, pressure […] and the increasing tempo of Chinese military exercises,” including a U.S. wish list for the defense budget to go as high as 10% of GDP, which they qualified as “completely unrealistic.” One forecaster also noted that U.S. pressure may weaken by 2027 as Trump approaches the end of his second term, reducing one of the upward drivers on Taiwan’s defence spending. Another referenced recent U.S. arms deals and a $2B package, arguing that “achieving higher defense spending through the acquisition of advanced systems is easy from the perspective of available systems to buy,” though delivery timing and technology sensitivities (e.g., limits on F-15s/F-35s) constrain how much can actually be absorbed by 2027.

A further wrinkle mentioned was GDP volatility, especially linked to TSMC and global chip demand: one forecaster noted that TSMC accounts for around 20% of GDP and warned that “a sudden change in the demand/price/supply could alter the defense spending as a percentage of GDP.” This volatility contributed to relatively wide confidence bands across estimates.

Question 4: Will any TSMC fab in Taiwan be destroyed or rendered inoperable for ≥90 days by 31 December 2027?

Forecasters saw a sharp contrast between the baseline and blockade-conditional risks: Aggregated forecasts clustered at 3.7% (with estimates between 0.8% and 14%) in absence of blockage, and jumped to 59% conditional on a blockade (with estimates between 30% and 90%).

Absent a crisis, forecasters regard a 90-day shutdown of any TSMC fab as unlikely, given TSMC’s resilience, supply buffers, and the fact that semiconductors are “too precious for everyone, including the attacker.” Once a sustained blockade is assumed, however, most judged it more likely than not that at least one fab would be offline for three months or more, mainly due to energy and input shortages and, in some scenarios, deliberate damage or “kill switch” use.

Low baseline risk: TSMC is resilient and highly valued

In the standalone forecasts, all forecasters are in the single digits, but for one higher outlier at 14%.

Several emphasized that China is unlikely to want to damage “one of the best prizes it could get from the island.” A forecaster at 5% wrote: “Semiconductors are too precious for everyone, including the attacker, which is a very unique situation.”

Others stressed the difficulty of a 90-day disruption threshold. One at 0.8% noted that even severe cyberattacks or power failures in advanced economies (e.g., a weeks-long factory shutdown, a major regional blackout) are typically resolved far faster than three months, and expects TSMC would “have production back online before 90 days.” Another at 2% allocates ~1% to extreme natural disasters and ~1% to a rare Chinese attack without blockade, calling it “an extremely low probability event” outside those tails.

Natural disasters, cyber incidents, and isolated sabotage were all mentioned, but forecasters consistently framed them as low-probability, short-lived shocks rather than likely causes of multi-month shutdowns.

Under blockade, energy and input chokepoints drive long outages

Once a sustained blockade is assumed, most forecasters shifted sharply upward.

Several stressed Taiwan’s energy dependence and limited reserves as a possible shutdown cause. One forecaster (at 58%) noted that Taiwan imports the vast majority of its energy and that LNG stocks cover roughly 10-11 days, coal would cover 39 days, and oil about 146 days. In a successful blockade, “power rationing would likely begin within one week,” forcing the government to prioritize essential services over industrial output: “production at TSMC would be among the first major industrial casualties.” Another, at 90%, similarly argued that “energy would be conserved for uses other than chip manufacturing and […] at least one fab would be shut down,” with both energy and critical materials (gases, chemicals, specialty components) unavailable for months.

Others emphasized that even without kinetic strikes, a sustained blockade would quickly break down the supply chains needed for continuous fab operation. A forecaster at 72% expected that “in a blockade scenario that is sustained, and not a small 8-day operation […] production at TSMC would almost certainly stop,” as electricity rationing, mobilisation of personnel, and disrupted imports compound. Another, at 73%, added that all sides have incentives at various points to shut the plants temporarily: to conserve resources, deny benefits to the other side, or as part of sabotage and cyber operations.

Another forecaster highlighted that Taiwan’s water supply is already tight, making it a natural target for sabotage and an additional vulnerability for water-intensive fab operations.

On the lower-end, conditional estimates reflected the view that, while accidental or indirect damage is possible, China would be reluctant to strike the fabs directly at the outset of a blockade, given the global economic fallout and the value of TSMC as a potential prize.

Deliberate damage, ‘kill switch’, and denial strategies in escalation scenarios

Conditional forecasts also considered scenarios where deliberate damage or self-sabotage drives long-term inoperability.

Some saw a significant chance that, in a blockade-that-escalates-to-war scenario, TSMC could be damaged as collateral or by design. One forecaster at 45% noted that while China might want to preserve TSMC as a “huge economic prize,” it could also see destroying or disabling it as a way to “force Taiwan to capitulate,” and that Taiwan might “intentionally damage its own fabs if it fears that the island will fall.” One forecaster also flagged low-probability scenarios in which China might move against TSMC preemptively if it feared the U.S. was on the verge of achieving AGI supremacy and saw crippling advanced chip supply as a way to slow that trajectory.

Others discussed rumours or reports of remote “kill switches” for advanced lithography equipment. A forecaster at 45% suggests that “rigging factories with explosives would be fairly easy” and that such sabotage would likely produce months-long outages given how sensitive advanced chip manufacturing is. Another at 62% mentioned a “not too far-fetched possibility that China’s hack (or Taiwanese themselves) executes the rumored ‘kill switch’,” and argues that China “would not care that much” about keeping TSMC operable if a world without TSMC left it relatively better off in semiconductors.

There was also some discussion of a U.S. action: forecasters mentioned the possibility for the U.S. to destroy or disable fabs to prevent them falling into Chiense hands, as mentioned by some officials, despite Taiwan being clear on the fact that they won’t allow it. with one forecaster assigning ~5% (within their high overall conditional probability) to these scenarios.

The forecaster stressing this scenario also argued that, over time, the U.S. is diversifying its chip supply and China is building its own capacity, making such a drastic step less attractive. As U.S. dependence on TSMC gradually falls, they suggested, Taiwan’s “silicon shield” will weaken, and U.S. incentives to both defend and to destroy TSMC facilities will change, though mostly beyond this forecast horizon.

Question 5: What percentage of TSMC’s employees will be located in the US or allied countries by 31 December 2027?

Forecasters expected modest but steady internationalisation of TSMC’s workforce by 2027, but not a dramatic shift away from Taiwan. Baseline forecasts cluster around 11-12% of employees in the US and other listed countries by end-2027, with individual point estimates between 8.5% and 12.5%. Conditional on a PRC blockade of Taiwan by mid-2027, the central expectation nudges up to around ~15%, with forecasts ranging from 7.5% to 17.5%.

In both cases, forecasters saw Taiwan remaining TSMC’s main employment hub, with overseas fabs in the US, Japan, and Germany still ramping up. The conditional forecasts mainly reflect tail scenarios (from forced relocation and shutdowns to rapid ramp-up abroad) rather than a clear, directional consensus that blockade automatically pushes large numbers of employees overseas.

Gradual international expansion from a low base

For the baseline, forecasters started from the observation that TSMC remains overwhelmingly Taiwan-based, with 84,500+ employees, of whom only ~7-8% currently work outside Taiwan and china. Several noted that this overseas share has been rising, increasing from ~4% in 2022 to ~7.5% in 2024, but still from a relatively low base. Japan is up roughly 500% (+1500 employees), North America up ~76% (+1900). Taiwan still accounts for the most net growth with +6,800 employees in 2024 alone.

New fabs in Arizona, Dresden, and Japan are expected to add thousands of jobs in the next few years. One forecaster projected that “at least 5,000 new foreign employees” could be hired by end-2027, while total headcount might reach around 100-105k, which would put foreign-based staff around 11%. Another argued that with plants in Arizona, Germany and Japan “in various stages of development,” it is reasonable to expect the share abroad to reach “10-12% by EOY 2027, absent a major crisis.” Forecasters also mentioned practical obstacles (long lead times, complex planning requirements, and the need for new grid connections) that constrain how quickly overseas facilities can absorb significant numbers of employees. One forecaster cautioned that technicians and production-line staff are usually hired last, while support and administrative roles are recruited earlier, meaning overseas headcount may rise even if some plants are not yet producing chips by 2027.

Overall, baseline reasoning treated gradual ramp-up of overseas fabs as the main driver: chips remain overwhelmingly made in Taiwan, but headcount abroad rises a few percentage points as new facilities approach or begin production.

Structural constraints and friction on moving workforces abroad

A second theme is that structural and political constraints will limit just how far and how fast TSMC can shift its workforce.

Several forecasters emphasised Taiwanese political preferences and “the overwhelming desire of the Taiwanese government to keep TSMC’s most important employees and chip production within Taiwan.” One noted that TSMC and its engineers are central to the island’s bargaining chip with the US and Japan: the more talent leaves, the weaker Taiwan’s leverage. From this angle, large-scale relocation of key staff is seen as strongly against Taipei’s interests.

Others pointed to operational and cultural friction in overseas expansion. One forecaster, sceptical about substantial expansion in North America and Europe, cited reports of tensions between TSMC’s management style and US labour expectations, arguing that “the push to diversify TSMC geographically faces serious hurdles.” European labour laws are seen as even more challenging. These factors led them to frame 7.5% (2024 levels) as a plausible floor and 13% as a plausible central case, with “a skew to the right” but no expectation of a dramatic jump.

Several forecasters also argued that fab construction and ramp-up are slow, multi-year processes. One sees “no realistic chance of significantly more automation” that would change overall headcount structure by 2027, and another expects only “a small increase in overseas employment to facilitate plant construction,” putting their baseline at 8.5%.

Together, these arguments underpin the baseline: a modest rise to roughly 10-12% abroad, but no dramatic re-anchoring of TSMC’s workforce away from Taiwan by 2027.

Under blockade, uncertainty explodes but median shifts only modestly

Conditional on a Chinese blockade by mid-2027, the majority of forecasters agreed that “bets are off.” The big change in the estimates is not a clear directional shift, but dramatically higher uncertainty about both the numerator and the denominator (who counts as a TSMC employee, and where).

Several forecasters explicitly said they kept the mean roughly similar but widened the variance. One explained that in blockade scenarios, “the tricky part here is arguably the denominator: what will happen, both to the fabs themselves as well as to the TSMC corporate entity?” Given “formidable uncertainty” and “too many moving parts,” they chose to leave the mean close to baseline (~12%) while significantly increasing the tails. Another similarly nudged their estimate only slightly upward (from 12.5% to 13%), explaining that a blockade could lead either to destruction and layoffs (reducing total employment) or to a long-term “escape from Taiwan” push, and they see “everything in between” as possible.

Others emphasised competing forces that could push the overseas share up or down:

Upward drivers:

Loss of China-based employees (some of TSMC’s ~4,000 staff in China being laid off or redeployed), potentially raising the share in US-aligned countries by “1.5% if not more”.

Partial evacuation of staff from Taiwan if a blockade or invasion seems imminent, or post-crisis efforts to ramp up production abroad.

Increased investment and hiring overseas to hedge geopolitical risk and maintain revenue streams.

Downward / countervailing drivers:

The Taiwanese government’s strong incentive not to let key TSMC staff leave, to preserve both the “silicon shield” and a mobilisable reserve.

The possibility that, in a defeat or capitulation scenario, TSMC “may survive as an entity but cease its operations in the US and other formerly allied countries,” reducing allied-country headcount.

Scenarios where fabs in Taiwan are damaged, shut down or split off, radically changing total headcount or corporate structure.

Most TSMC staff would likely remain in Taiwan simply because a blockade or attack would arrive too quickly for meaningful evacuation.

The risk of engineers fleeing with sensitive information is probably overstated, as much of the relevant know-how is already known to major intelligence agencies.

TSMC employees might be drafted into Taiwan’s armed forces during a prolonged crisis, temporarily reducing the civilian workforce and complicating the interpretation of employment shares.

One forecaster at 17.5% conditional stressed the potential disappearance or reassignment of thousands of China-based employees and a possible push to “increase TSMC’s efforts abroad,” but remained uncertain, putting 50% of their forecast between 7% and 20%. Another, at 15-16%, laid out multiple invasion paths: from “no change” (TSMC continues to operate broadly as before) through temporary shutdowns to rarer cases in which TSMC splits or shuts down some overseas operations.

A recurring point in discussion was that timing matters: a blockade in early 2026 leaves more time to adjust headcount than one launched in late 2027, and outcomes will differ sharply depending on whether a blockade quickly escalates to war, ends in negotiated de-escalation, or drags on.

Conclusion

Taken together, these forecasts point to a tense status quo through 2027. Forecasters see low-but-real risks of a blockade or major disruption, yet expect Taiwan to avoid dramatic political moves, keep defence spending on a gradual upward path, and retain both TSMC’s core capacity and workforce on the island.

The more dramatic shifts – prolonged fab shutdowns, large-scale relocation of engineers, or sovereignty moves under duress – mostly sit in conditional or tail scenarios, especially those involving a sustained PRC blockade.

If you have comments on this analysis, or would like to see these questions re-posed with different timeframes, conditional events, or additional indicators, please drop us a line at [email protected]